Empathy

Conflict Resolution Network

Objectives

- Objectives:

-

- To understand the concept of empathy.

- To explore communication patterns which block and which foster empathy.

- To develop and practise the skill of active listening.

Session Times:

- 2 x 3 hours:

- Sections A–E

- Sections F–K

- 3 hours:

- Section A–E or

- Sections A and C–I or

- Sections F–K

- 1 ½ hours:

- Sections A, B, D, E and F

- 1 hour:

- Section A, D and F

Essential Background:The Win/Win Approach

- Sections:

- A. Exploring the Meaning of Empathy 3.3

- B. Valuing Differences the DISC Exercise 3.4

- C. Introduction to Empathy Blockers 3.4

- D. Detailed Look at Empathy Blockers 3.5

- E. Concluding Discussion: Empathy Blockers 3.6

- F. Introduction to Active Listening 3.7

- G. Listening to Gain Information 3.9

- H. Asking Questions 3.9

- I. Listening to Give Affirmation 3.11

- J. Listening When under Verbal Attack – to Deal with Another’s Inflammation 3.14

- K. Reflection on Listening 3.16

- Activities:

- The DISC ExerciseA.3.1

- Blocking CommunicationA.3.9

- Experiencing Empathy BlockersA.3.10

- Experiencing the Difference Between Empathy Blockers and Active ListeningA.3.12

- StaticA.3.14

- Back-to-Back DrawingA.3.15

- Shopping ListA.3.17

- Identifying Feelings and RespondingA.3.19

- Active Listening to AffirmA.3.20

- Handouts:

-

- Section B:

- Section D:

- Section E:

- Section I:

- Section K:

Empathy

Understanding and Valuing Individual Differences

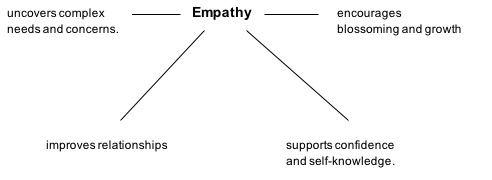

A. Exploring the Meaning of Empathy

(20 minutes)

Question:What does the word “empathy” mean?

Discussion:Encourage a few minutes’ discussion to arrive at a common understanding of the term. Ask how it is different from sympathy. Empathy is ”feeling into”, seeing how it is through another’s eyes.

“Empathy is walking with another person into the deeper chambers of his self – while still maintaining some separateness. It involves experiencing the feelings of another without losing one’s own identity. It involves accurate response to another’s needs without being infected by them…[The empathic person]…senses the other person’s bewilderment, anger, fear or love as if it were his own feeling, but he does not lose the ‘as if’ nature of his involvement.” Robert Bolton People Skills (Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 1987) p271.

Question:Think of someone with whom you often feel empathy. What helps you to feel empathy? What are some of the ingredients?

Discussion:Ask participants to write down their answers. Share in pairs and then in the large group. In addition, you might consider:

- trust

- attentiveness

- appropriate responses

- shared experiences

- respect

- support

Question:Think of someone with whom it’s difficult to feel empathy. What does that feel like? What are the ingredients?

Discussion:Ask participants to write down their answers. Share in pairs and then in the large group, using additional questions to explore further.

What makes it difficult?

What are the things that block you off from that other person?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- inattentiveness

- talking about him/herself

- lack of interest

- low respect etc.

It may be that we sometimes have difficulty developing empathy because we don’t know how to respond to a person’s behaviour. We may not know how to be when we’re with that person. The emphasis here is on our response – it’s not blaming or finding fault or inadequacy with the other person.

Question: What are the key elements of empathy as a skill?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- Separate our responses from those of the person with whom we are empathising. Retain objectivity and distance.

- Be alert to cues about feelings offered to us by the other person.

- Communicate to people our feeling for them and our understanding of their situations.

B. Valuing Differences – the DISC Exercise

(1 ½ hours)

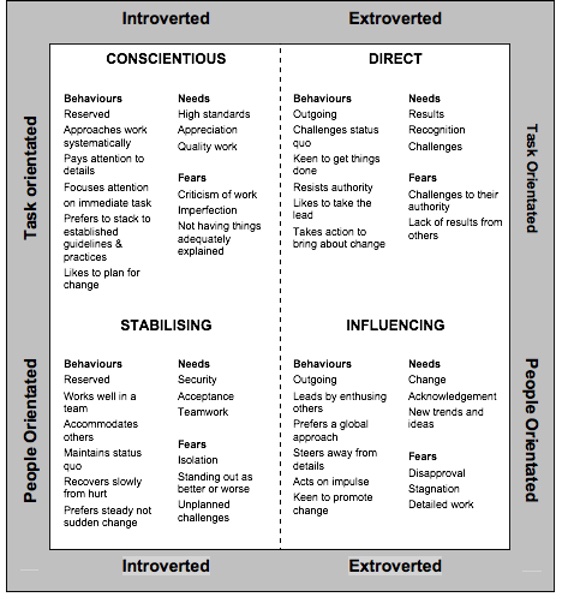

The DISC Exercise: this provides participants with a framework for recognising and valuing different behavioural styles. Understanding others’ approaches to completing work, to problem-solving, to managing priorities, to dealing with feelings and so on, can help build empathy, relieve tension and minimise conflict. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.1 for details.)

C. Introduction to Empathy Blockers

(15–25 minutes)

Below are two approaches. Normally use only one of these unless you are running an extended session on Empathy, or if the group is having difficulties grappling with it.

Approach 1

Question:Think of a time when you wanted to tell someone something and the response from the person helped the communication significantly. What was the person doing?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- really listening

- asking questions

- using ”mms” and ”ahs” to encourage

- maintaining good eye contact

- displaying attentive and welcoming body language.

Question:Now think of a time when you wanted to tell someone something and what that person did in response made you shut down your communication with them. What wasn’t working?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might explore:

- not really listening

- not showing interest

- being inattentive

- having poor eye contact

- changing the topic

- giving advice.

Approach 2

Group Activity:Blocking Communication: participants working in small groups of three explore the ways we sometimes block communication. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.9.)(15 minutes)

D. Detailed Look at Empathy Blockers

(30–40 minutes)

We’ve been considering behaviours and comments that inhibit communication. We’ve come up with a variety of non-verbal behaviours – body language, eye contact, physical barriers, and we’ve also touched on some of the verbal inhibitors like (refer to examples that came up in Section C, if any)…giving advice…reassuring and so on. We call these empathy blockers, and we’ll now give these some more attention.

Question:Think of a phrase or phrases that might really irritate you, or at least cause you to shut down. What are they?

Discussion:Share these in the group. Then give out the handout: ”Empathy Blockers”.

Ask participants to read through the handout and identify empathy blockers they use or that someone else uses.

Group Activity:Choose one of the three approaches below, using the Empathy Blockers handout.

Pair Share: ask the group to form pairs and share their responses to particular empathy blockers e.g. Which ones block them most? What responses do they arouse?(10 minutes)

Experiencing Empathy Blockers: small groups deliberately block empathy with a person who is relating an issue of concern. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.9.)(20 minutes)

Experiencing the Difference between Empathy Blockers and Active Listening: working in pairs, two rounds enable participants to experience the difference between empathy blockers and active listening. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.12.)(20 minutes)

E. Concluding Discussion: Empathy Blockers

(20 minutes)

Question:What are the consequences of using empathy blockers, on communication, on the people involved, on problem-solving?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- results in defensiveness, resistance and resentment

- blocks feelings

- diminishes self-esteem

- decreases the ability to solve problems

- creates emotional barriers between people.

Question:Given that empathy blockers tend to have negative effects, why do we use them?

Discussion:You might stimulate the group’s thinking by further questioning.

Are there times when we’re more likely to use empathy blockers? What are they? (After participants have responded, you might add: when under stress, or feeling angry, frustrated, out of control, and out of habit.)

Why don’t we use more effective communication methods, like active listening and assertiveness? (After participants have responded, you might add: high emotion, conditioned responses modelled on those closest to us during childhood (like parents and teachers), deliberate desire to hurt or manipulate.)

Important Points to Cover:

With awareness of our use of empathy blockers we can choose to try more effective methods of communicating.

When we use an empathy blocker or shut down our communication when an empathy blocker is used on us, we are probably relying on a habitual and automatic way of behaving we learnt in childhood. We react. But, when we pause a moment and choose a response that opens rather than closes communication, then we can respond.

Write on the board:

REACT

or

RESPOND

By choosing to respond, we’re taking control of our behaviour and opening the door to richer relationships.

Once we’re responding rather than reacting, there can be times when offering reassurance or giving advice can be helpful. Those times come after you’ve listened and others know they’ve been heard, and after you’ve shown them respect and recognised how they’re feeling. Reassurance and advice may then be given in a cautious, constructive and supportive manner that empowers them to do what they need to in order to move on.

Give out the handout: “Create Empathy”.

F. Introduction to Active Listening

(30 minutes)

Optional Activity: Depending on time and the needs of the group, use one of the following stimulus activities:

Static: participants pass a message from one person to the next. The last person will often repeat a message quite different from the original because of selective listening differences in interpretation etc. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.14.)(15 minutes)

Back-to-Back Drawing: participants try to reproduce a drawing with only verbal instructions. This can be difficult because we all have different perceptions of what words mean. As well, we readily make assumptions to fill in the gaps in what we hear. (This activity can also be used in Section G: Listening to Gain Information or Section I: Listening to Give Affirmation.) (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.15.

(20 minutes)

In considering the topic of empathy we’ve looked, so far, at the importance of recognising and valuing different behavioural styles – DISC. We’ve also looked at the ways that impede or block empathy. We now want to focus on a skill that helps to create and foster empathy – the skill of listening.

Question: Who’s familiar with the concept of active listening?

Discussion: Raise your hand to indicate that’s what you want participants to do.

Question: Who believes they could improve their skills in active listening?

Raise hands as above.

Reflection: Think about yourself as a listener. Now think of five people with whom you interact on a daily basis. On a scale of 1–10, with 1 for poor listening skills rate how each of those people would perceive your listening skills.

Discussion: Allow 2 minutes and then encourage discussion by asking questions:

Question: Would you expect different people to rate you differently? What factors affect your ability and/or willingness to listen effectively?

Discussion: Draw out participants’ responses. In addition you might consider:

- relationship with speaker

- lack of time

- pre-occupation with other matters

- difficulty dealing with emotions – theirs and yours

- strong disagreement

- environment

- physical discomfort.

Which scores do you consider worth improving?

Question: How do we know when someone is really listening to us? What is it like?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- eye contact

- verbal responses

- asking relevant questions

- posture

- gestures, nods

- future actions

- feelings of being valued, heard, cared for.

These can be explored in more depth in sections G–J.

Pair Share:Ask the group to spend 5 minutes with a partner sharing their responses to the following two questions:

What things about listening do you think you manage well?

What would you like to improve about your listening skills?

G. Listening to Gain Information

(30 minutes)

We listen for a variety of reasons. One of the main reasons is to gain information. Sometimes conflict can develop because vital information is missing or miscommunicated.

Studies have shown that immediately after people have listened to someone talk, they remember only about half of what they’ve heard. Then, within eight hours, they tend to forget one half to one third more of what they have heard. (Studies conducted at the University of Minnesota in 1957 by R Nichols and L Stevens quoted in Robert Bolton People Skills Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 1987, p30.)

Group Activity: Choose either one of the following two activities:

Shopping List: working in pairs, Partner A asks Partner B to buy five items. If Partner B asks clarifying questions, Partner A is more likely to receive precisely what he/she wants. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3. 17.)(15 minutes)

Back-to-Back Drawing: participants try to reproduce a drawing with only verbal instructions. This can be difficult because we all have different perceptions of what words mean. As well, we readily make assumptions to fill in the gaps in what we hear. (This activity can also be used in Section F: Introduction to Active Listening or in Section I: Listening to Give Affirmation.) (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.15.)

(20 minutes)

H. Asking Questions

(10 minutes)

Too often we rely on others to give us all the information we need; or we have too much faith that we are using words in the same way. We may, in fact, be attaching different meanings or very different pictures to words.

Sometimes conflicts arise because of differing perceptions of what words mean. For example:

lf you were asked to clean up a particular area, does that mean make it tidy, put things in neat piles, or put things away? Does it include dusting and vacuuming? Does it mean moving the furniture, or just cleaning the exposed surfaces and so on?

All parties in a communication have a role in making things clear.

Asking questions helps us to become specific.

A useful shorthand for gathering information is to think in terms of:

Write on the board:

HOW?

WHY?

WHAT?

WHERE?

WHEN?

Which of these are relevant and need to be answered? How can they be asked so as to elicit information and not cause defensiveness?

The way in which a question is constructed determines its usefulness. Closed questions elicit specific information and are valuable when this is what is required. Open questions encourage broader exploration of the issue and associated feelings.

For example, a closed question such as:

“Would you like things to be different?”

elicits a yes/no answer.

An open question, such as

“How would you like things to be different?”

is more likely to encourage others to talk. It demonstrates our interest in their ideas, and gives us much more of a window into their thinking, which is the foundation of empathy.

Use of the word “why” can inflate conflict, and so needs to be used with caution.

A question out of context, and blunt, such as “Why were you late this morning?” can cause the other person to become defensive and close down. Can this enquiry be phrased differently and preceded by a statement of our need for punctuality? Or could it focus instead on what can be done to avoid being late in the future? Or…? There are many alternatives which can be built on acknowledging that the other person has a perspective that needs to be explored.

Group Activity: Practice on Constructing Open Questions: participants consider examples of closed questions and try to think of open alternatives. (See below for details.)(5 minutes)

I’m going to give you a series of closed questions. I want us then to try and construct some open alternatives. e.g.:

Give one example at a time, and ask participants for alternatives.

- Do you want to resolve this?

- Have you got something to say about this situation?

- Do you like the design of the new poster?

- Was the conference interesting?

- Have you had a good day?

End this activity with a group discussion about difficulties, insights, and comments.

I. Listening to Give Affirmation

(1 hour)

Stimulus Activity:Back-to-Back Drawing: participants try to reproduce a drawing with only verbal instructions. This can be difficult because we all have different perceptions of what words mean. As well, we readily make assumptions to fill in the gaps in what we hear. (This activity can also be used in Section F: Introduction to Active Listening or in Section G: Listening to Gain Information.) (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.15, for details.)(20 minutes)

So far, we’ve discussed active listening for the purpose of gaining information.

Write on the board:

ACTIVE LISTENING:

to gain information

Now we’re going to change focus to think about listening to affirm another person.

Write on the board under “to gain information”:

to give affirmation

Question:What do we mean by giving affirmation to another person?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- acknowledging another

- making another feel valued

- showing empathy.

In a conflict situation often the most important need for another person is to sort out ideas using us as a sounding board. As well, we may be needing to hear the details of that person’s feelings and thoughts, to really understand a different perspective – so that we can show empathy.

Question: What skills show that we are listening to another person with empathy?

Discussion: Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might explore:

Non-verbal skills environment

body posture

eye contact

encouraging gestures

Following skills: minimal encouragers, such as ”mm” and ”ah”

occasional questions

attentive silences

Reflecting skills: reflect back feelings and content

paraphrase

summarise

use a tone of voice that shows warmth and

interest.

Reflecting back feelings and content, using our own words, is the crucial skill in listening to affirm.

Question: Why is reflecting back so crucial?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- to make sure we hear exactly what is intended

- to show empathy

- to help the other person hear him or herself.

Question:How do we reflect back?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition you might explore:

- not parroting the person’s words

- para-phrasing and summarising.

Give some examples to explain this more fully.

Asking too many questions can distract the speaker, and lead in a direction that may be of more interest to the listener. It can be appropriate to ask questions, provided they are very closely linked to what the speaker is saying and supportive to the crucial skill of reflecting back.

Group Activity: If time permits, and it is appropriate to the group, do both activities listed below. If not, omit the first one, and do only the role play.

Identifying Feelings and Responding: participants consider a list of statements to identify the underlying feeling being expressed and to work out an appropriate active listening response. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.19.)(10 minutes)

Active Listening to Give Affirmation: Working in pairs, participants have the opportunity to practise their listening skills and to be listened to. (See Empathy Activities, p A.3.20.)(40 minutes)

Important Points to Cover:

Good listening empowers speakers. It helps people verbalise what may not have been clear to them before. People can usually find their own answers. They are more likely to put their own plans into action rather than someone else’s well intentioned advice.

When people feel listened to, they will talk more freely about themselves. Even well-intentioned advising or diagnosing may block this communication.

Active listening may entice people to reveal more of themselves than they are really comfortable doing. They may later be highly embarrassed and distance themselves from the listener. lt is important to respect people’s comfort zones in personal communication. This applies particularly to work contexts where people often prefer to be private about personal issues.

There is a time to active listen, and there is a time to graciously add in our own perspectives. Look for cues from the other person to know when this is appropriate.

Really listening is far more than waiting for our turn to speak. We put so much attention on the other person that our own mental commentary is ”turned off” at that time.

Give out the handouts: “Active Listening… Some Helpful Hints” pH3.7 and “Active Listening for Different Purposes” pH3.8

J. Listening When under Verbal Attack – to Deal with Another’s Inflammation

(40 minutes)

Note: It is often useful to teach this section of Active Listening in the broader context of Managing Emotions. By then, participants will have had the opportunity to practise listening for information and to give affirmation before facing the challenge of dealing with high emotion.

For those wishing to include it in this section, notes are set out below.

Question: When someone is verbally attacking us, what are our usual responses?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might explore:

- becoming defensive

- becoming aggressive

- arguing in a heated way

- retreating into ourselves

- becoming upset, fearful.

Question: How effective are these responses in dealing with the other person’s anger, and in resolving the conflict?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- often doesn’t lead to a solution; or at best only leads to a short term solution

- may have long term detrimental effects on the relationship

- results in feeling drained or upset or downtrodden

- increases the likelihood of this pattern repeating itself.

When there is a conflict, it’s common to blame the other person or become extremely defensive. It is difficult to be objective when the emotional level is high. Active listening is an effective tool to reduce the emotion involved in a situation.

Write on the board:

ACTIVE LISTENING:

to gain information

to give affirmation

to respond to inflammation.

When we accurately identify and acknowledge an emotion, the intensity of it dissipates like a bubble bursting or a grease spot dissolving. The speaker feels heard and understood. Once the emotional level has been reduced, reasoning abilities can function more effectively.

Write on the board:

High Emotions?

Active Listen to

deal with emotions

FIRST.

Carefully using active listening can turn the situation of conflict around to one of co-operating so as to develop new options.

Group Activity:Handling Another Person’s Inflammation: in this role play, participants practise their active listening skills. (See Managing Emotions Activities, Handling Another Person’s Inflammation, p A 6.6.)

(20 minutes)

Important Points to Cover:

This active listening technique is very valuable when we are receiving non-verbal gestures of anger (e.g. turning away, rolling the eyes…”Are you fed up with the situation?” “What’s annoying you?”)

There is great value in allowing angry people to be really heard whether or not we feel their attacks are justified.

First bring down the emotional heat and avoid making statements of attack or defence that would cause a crisis to escalate.

When we fully understand the problem we can respond more effectively. This may include pointing out errors of fact or interpretation. This sounds quite different to defence or counter-attack.

The aim is to improve communication in the relationship, both people hearing and being heard. When tempers are calmer, then real communication can begin.

Staying calm during a personal attack takes skill. This is a skill which can be learnt and needs persistent practise.

The point of change in a conflict situation is the point of communication. At this stage, the discussion can turn to: What do you need, not need? What do I need, not need? Can we fulfil these needs?

It’s about being

Write on the board:

Hard on the problem

Soft on the person

and turning the conflict into

Write on the board:

Partners not opponents

K. Reflection on Listening

(2 minutes)

Read the poem on the handout: “Listen”.

Empathy Activities

The DISC Exercise

Trainers Information OnlyContext: The skill of empathy enriches interpersonal communication. When we can see how it is from the other side, we can often resolve the issue to everyone’s satisfaction more easily, and learn to value our differences. (See Chapter 3, Empathy Section B) Time: 1 ½ hours Aims:

Handouts: “Behavioural Style Questionnaire” (if using Method 1 below) and “DISC Model” Requirements: Sufficient clear space for participants to move around. |

Instructions: In this activity, you will be asked to move to one of four areas in the room. Each area represents a particular behavioural style. It is not about labelling or being categorised, but about tendencies. We all have aspects of each style but tend to lean towards one particular style especially when under stress. As well, we move In and out of each style depending on the situation. We may have a favourite style in our working environment and quite a different one at home. No behavioural style is better or worse than any other; each has its own strengths. Moving into one area is not a final decision. At any point during the exercise participants may change areas.

The purposes of the activity are:

- to consider the different types of behaviour we choose in different settings

- to identify the behavioural styles we frequently use

- to understand behavioural styles that are different from our own.

- Split the group into four areas using one of the two methods below.

Method 1

Give out the handout: “Behavioural Style Questionnaire”.

For this exercise you need to think about your behaviour in a specific setting. You behave differently in different settings. Think of how you behave at work, (or at home, in this organisation etc.). In particular, think how you behave during periods of pressure.

Quickly go through each of the four styles, marking those words or statements which describe the way you behave at work (or in the chosen setting.) Only tick those that you immediately or most clearly recognise. Don’t ponder or change your responses too much. The spontaneous answer usually gives the best indication of where you place yourself today.

Now add up the number of marks in each section.

We are now going to move to different areas of the room.

Divide the room mentally for yourself as per the handout: “DISC Model”

|

Trainer at front of room |

|

|

C

|

D |

|

S |

I |

and direct people to the appropriate area.

Those with most marks in the section that starts ”Gives priority to achieving results”, move to the front of the room, on my left. (Trainer points) Those with most marks in the section that starts ”Gives priority to creating a friendly environment’, move to the back of the room, on my left. Those with most marks in the section that starts ”Gives priority to supporting others” move to the back of the room, on my right. Those with most marks in the section that starts ”Gives priority to detail and organisation”, move to the front of the room, on my right.

Some participants may have two sections with the same ”highest” score. Do they feel they relate to one overall list better? Or do they feel they’re more extroverted or introverted task or people oriented? If they can’t decide, ask them to go to one of their highest scoring areas and, as the exercise proceeds, they may become clearer and can move if they choose.

Method 2

For this exercise you need to think about your behaviour in a specific setting, as you behave differently in different settings. Think of how you behave at work (or…at home, in this organisation etc.)

Ask the group:

Would you describe yourself as:

- more reserved and reflective – MOVE TO YOUR LEFT

(Trainer’s right)

Or

- more outgoing and extroverted – MOVE TO YOUR RIGHT

(Trainer’s left)

Then to the entire group:

Staying on your side of the room, move either to the front or the back, according to the descriptions I give you now. Listen to the entire description and feel where you most comfortably fit. Don’t latch onto one word or phrase by which to include or exclude yourself. You’re looking for the best general description of you.

To the more outgoing group:

Would you describe yourself as someone who tends to:

- seek challenges

- tell it how it is

- get the job done fast and efficiently

- focus on achieving results

- take initiative?

– MOVE TO THE FRONT OF THE ROOM

Or as someone who tends to:

- generate enthusiasm in others

- like working with others

- make sure there’s time to talk

- focus on an overall vision

- skim over the detail?

– MOVE TO THE BACK OF THE ROOM

To the more reserved group:

Would you describe yourself as someone who tends to:

- pay attention to detail

- approach tasks systematically and thoroughly

- set very high standards

- think critically and analytically

- organise tasks, files, drawers, cupboards etc very well?

– MOVE TO THE FRONT OF THE ROOM

Or as someone who tends to:

- work well as part of a team

- make yourself available for others

- maintain current arrangements

- take time to listen and consult

- smooth problems over to maintain good relationships?

– MOVE TO THE BACK OF THE ROOM

Small Group Discussion:

When the group has split into four areas, ask participants to consider the following questions in discussion with others in their area:

Think how you would approach another person who is causing you a difficulty. (e.g. your colleague hasn’t delivered the report he/she promised.) Think of what you would say, the time, the place, the setting etc.

Now, think of yourself as a person causing difficulty for someone else (e.g. you haven’t delivered a report that you had promised. Your colleague needs the report to proceed with his/her work.) How would you like to be approached?

Discussion: Ask participants in each area to share their responses with the large group. Note the words they use (perhaps on a board.) You could ask those in one area (e.g. D) how they would feel being approached in the manner another group (e.g. S) has described, and so on.

Small Group Discussion:

Ask each behavioural style to consider the following questions:

- What do you really like about your particular style? What do you think its strengths are?

- What do you feel uncomfortable about in your style? What do you think its limitations are?

- What do you value about the other styles in the room? What do you find difficult about them?

Discussion: Ask each area to share their responses with the large group.

Comment that one person’s need can hook into another person’s fear, and this can increase conflict e.g. this group’s (i.e. D) abrupt delegation of an ”out there in front” job can terrify this group (i.e. S) who fear standing out.

Can you think of examples of these hooks operating in your interactions with people?

IDENTIFYING THE BEHAVIOURAL FRAMEWORK (DISC)

By now, participants have had the opportunity to see a framework emerging. The trainer can name each of the behavioural styles – DIRECT, INFLUENCING, STABILISING, CONSCIENTIOUS – if this hasn’t already been done.

Give out the handout: ”DISC Model” and link the descriptions with previous discussion.

When we’re in conflict, we are often caught into thinking that we’re right and others are wrong. In fact, it’s often that others have a different way of approaching a difficulty, or that they need to concentrate on a different aspect of the problem before they move onto the part that we think is most significant.

Expanding our understanding of these differences, and valuing them, can help us to deal with conflict and to build a strong, co-operative approach to getting a job done.

When conflict is at the incident or misunderstanding level, we often hover in the centre of the behavioural styles, and adapt our behaviours readily and easily.

However, when we’re under stress, such as conflict at tension or crisis level, we will often rely on a more narrow set of behaviours.

Elaborate on the styles by telling the following humorous stories.

There is a major change in the office. It’s 9.00 o’clock, Monday morning. How is each group handling it?

Direct: They have been there for an hour already, working out how to achieve the changes with the utmost efficiency and speed.

Influencing: They aren’t in the office yet. They are downstairs in the coffee shop, talking with a colleague about something that will be very helpful in the change. They regard themselves as ”at work” already.

Stabilising: They hope it’s not going to be as disruptive as the last change. And they are not at all sure that everyone’s needs have been considered and accommodated in the plans.

Conscientious: In the change, a new piece of equipment had to be purchased. They’ve spent a busy three weeks investigating and listing the positives and negatives of every feature of every brand on the market. They’re sure they’ve made the right decision. Thank goodness the change has not thrown the filing system into disorder.

How does your group learn to swim?

Direct: They dive in the deep end. Lots of splashing, lots of action. The deeper the pool, the better. They take risks and show little fear.

Influencing: They have arranged to go with friends and have met them for breakfast beforehand. Learning with friends is sure to be more fun.

Stabilising: They tend to start on the edge of the pool with goggles and flippers. They prefer to be towards the back of the line to make sure others don’t miss out on their turn.

Conscientious: They spend weeks in the library researching anatomy and physiology of swimming to really know what they will be learning. In selecting a swimming teacher, they have researched their credentials, their years of experience, and their membership of relevant swimming associations to ensure the best possible tuition.

Group Activity: Differences in Behavioural Style: Participants complete a handout to identify people with whom they often find themselves in conflict. What behavioural style do they find them using?

Give out the handout: “Differences in Behavioural Style”.

Allow 10 minutes.

Pair Discussion:Encourage participants to share their responses with a partner.

Important Points to Cover:

It’s important to value differences. Different approaches lead to creative problem-solving. Understanding differences rather than judging them, encourages empathy, builds rapport, and helps build better relationships. ”You can complain the rose bushes have thorns or rejoice that thorn bushes have roses”. lt makes sense to look for the ”roses” in people.

Whilst we lean towards one particular style; we have aspects of all of them.

Recognise and use the strengths and limitations of each behavioural style rather than making judgements about right or wrong. Build upon strengths and move beyond or around limitations and biases.

Capitalising on strengths builds self-esteem and confidence. This enables people to acknowledge limitations, without being hindered by them.

In teamwork, at certain times it may be more effective to utilise the strengths and expertise of other team members than to take the time and effort that is necessary for us to develop these skills. When delegating tasks, be aware of people’s behavioural styles.

Ignorance of differences in behavioural styles can contribute to conflict. The more we understand and value the differences the easier it is to minimise difficulties.

Using a framework, such as DISC, can help to highlight individual needs and concerns. In a climate of co-operation, others are more likely to be supportive of our suggestions if they know that their needs and concerns have been considered.

Concluding Questions:

Think of a situation other than the one you originally considered e.g. home, member of a club or association. Would you use a different behavioural style in that setting?

Think back a few years. Would you have tended to use the same behavioural style, perhaps more or less strongly; or would you have used a different style more often?

If there’s been a shift, or if you would be using a different style dependent on the situation, why is that? (After participants have responded, you might add: new skills, conscious attempts to modify behaviour already, expectations of others, demands of particular roles.)

Final Comments: Stress that these are behaviours. To some extent we can choose to continue these behaviours, particularly where they serve ours and others’ purposes. Or we can add other behaviours to our repertoire so we can be more flexible.

Empathy Activities

Blocking Communication

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: We often use statements either consciously or unconsciously, to block communication with others. (See Chapter 3. Empathy: Section C.) Time: 10 minutes Aim: To become aware of the statements we make to block communication with others. |

Instructions: We’re going to do a role play to find out what we say and do when we are excluding someone from a conversation.

Ask participants to move into groups of three and choose who will be Persons A, B and C.

Persons A and B, you are sitting together having an important conversation (e.g. topic relevant to group – office politics, introduction of new procedure, what to do on Saturday night.)

Person C enters and persistently wants to join in the discussion. Persons A and B don’t want this. You do what you can to exclude Person C. Your aim is to have Person C leave.

Allow about 5 minutes and then bring them into the larger group.

Discussion: Ask participants to describe what happened.

Were Persons A and B successful in excluding Person C? How did you do it?

Persons C: Was there anything which you found particularly excluding?

How did it feel for each party?

Where was your focus: on the person or the problem?

What else could you have done to have your needs met?

Empathy Activities

Experiencing Empathy Blockers

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: Empathy blockers arouse different responses in different people. (See Chapter 2 Empathy: section D.) Time: 20 minutes Aim: To experience the effect of empathy blockers. Handout: “Empathy Blockers” Requirements: Sets of empathy blocker cards if using Variation 2. |

Instructions: Distribute the handout: “Empathy Blockers”. Ensure that participants understand the content.

In this activity, we will work in small groups to experience the impact of empathy blockers on conversation, and to become aware of the particular blockers we use and those which cause us to close down.

Divide into small groups of approximately five. Then give additional instructions according to one of the two variations below.

VARIATION 1

One person relates a problem (not too deep) and the other participants respond, in turn, using an empathy blocker of their choice.

Rotate roles so that each participant has a tum at receiving the group’s empathy blockers

VARIATION 2

The names of the empathy blockers are written on separate cards. One complete set per group is issued, and turned upside down. Participants other than the problem-relater draw a card each and respond with the empathy blocker named. ln debriefing, participants can guess what empathy blocker each person was using. If time permits, rotate roles. A topic can be given to the problem-relater.

Discussion: How did it feel to receive the empathy blockers?

How did it feel to use an empathy blocker?

Were some more familiar than others?

Were some more difficult to deliver than others?

Were some more difficult to receive than others?

What was your reaction?

Empathy Activities

Experiencing the Difference Between Empathy Blockers and Active Listening

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: Communication can be killed by empathy blocking statements and encouraged by active listening. (See Chapter 3. Empathy: Section D.) Time: 20 minutes Aim: To experience the difference between the effect of an empathy blocker; and the effect of active listening. |

Instructions: In this activity, we will work in pairs. Each person will have a turn at relating a concern or difficulty. The other person will respond first using empathy blockers and later using active listening.

Have group form pairs and choose Person A and Person B.

Round 1

Person A, you tell Person B something slightly upsetting or emotional which happened recently.

Person B, you respond with reassurance, attempting to make it better for Person A. For example: ”Oh don’t worry about it,” or “Let’s have a cup of tea, then you’ll feel better”.

Allow 2 minutes. Repeat the exercise using the same problem.

This time Person B, you practice empathy and active listening, really ”hearing” the speaker, using active listening skills.

Allow 3 minutes.

Round 2

Reverse roles.

This time the listener uses the empathy blocker of topping, giving examples of stellar situations, basically cutting off the speaker e.g. ”Yes, that happened to me too” or “I had a friend who…”

Allow 2 minutes. Then, repeat the problem using active listening.

Allow 3 minutes.

Pair Discussion: Ask pairs to discuss what they noticed. Allow 3–4 minutes.

Discussion: What came out of that exercise for you?

How were your feelings different when you were responded to with empathy blockers and then with active listening?

How did it feel for the listener using empathy blockers and then active listening?

Empathy Activities

Static

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: Meaning in communication is frequently lost or distorted if listeners don’t ask questions and check what they’ve heard. (See Chapter 3 Empathy: Section F.) Time: 15 minutes Aims:

|

Instructions: In this activity, we’re going to pass a message along a line. We’ll whisper, so only one person at a time hears the message. And at the end we’ll see if any distortion has occurred. This is like the ”static” or hiss in a bad telephone connection.

The group sits in a line or a circle, with some distance between each person. (lf the group is large, consider dividing it into two.)

The trainer reads a message (see below) to the first person, who whispers it to the next person and so on along the line.

The last person repeats it aloud to the group. The trainer then reads out the original message.

Two sample messages:

- They don’t want you to give them the house. They just need to use it because they are going into business and need all their capital. They feel you owe it to them. You could have a real problem if you fight this.

- Early one morning, a computer salesperson was driving a blue Porsche from Cabramatta to Penrith when the engine stalled. Getting out of the car, going into a chocolate shop, and explaining the difficulty, a sales assistant helped out by pointing to a yellow phone.

Discussion: How much of the original message was lost or changed in the telling of it?

What could be done to keep the message more intact?

What affects the understanding of a message? (After participants have responded you might add: emotions involved, prejudice, words used, context, number of elements, underlying intent of both speaker and listener, attention of the listener.)

Empathy Activities

Back-to-Back Drawing

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: We each have our own perception of things. In conflict it is our differing perceptions which often inflame the situation. Language is frequently an imperfect tool for conveying what we mean. (See Chapter 3 Empathy: Sections F, G and I.) Time: 20 minutes Aims:

Requirements: Blank paper, coloured pens. |

Instructions: In this activity, working in pairs, we’ll try to reproduce the drawing our partner does to explore some important features of communication.

Divide the group into pairs with Partners A and B sitting back-to-back.

Then give them additional instructions according to one of the three variations below.

VARIATION 1

Round 1

Partner A describes to Partner B what A has drawn. Partner A aims to give Partner B sufficient information for Partner B to accurately reproduce the drawing. B remains silent.

Allow 3 minutes. Then reverse roles.

Round 2

Partner A describes the drawing as before. This time partner B asks questions and reflects back to partner A.

Allow 5 minutes. Then reverse roles.

VARIATION 2

Two rounds as above, only allowing description of the parts of the drawing e.g. not ”it’s a house”, but “it’s a square with a triangle on top”.

Allow 3 minutes for each step in Round 1, and 5 minutes for each step in Round 2.

VARIATION 3

Partner A you draw a picture. The aim is for Partner B to reproduce Partner A’s drawing. There are only two rules; one, pairs must stay back-to-back; and two, pairs must not look at each others drawings until I tell you the time is up.

Allow 3–5 minutes. Then reverse roles.

Discussion: Choose questions appropriate to the variation you used. If you used Variation 1 or 2, you may want to insert some discussion between Rounds 1 and 2.

Did either Partner A or Partner B feel confused or frustrated? Why? What caused this confusion to arise? (After participants have responded, you might add, pre-conceived notions, differing perceptions and assumptions, different understandings of terminology like inches/centimetres, Partner A leaving out important details etc.)

What was it like not to see each other? (Non-verbal components are intrinsic to communication. ln many cases, non-verbal communication is more powerful than verbal e.g. in conveying emotions, attitudes, reactions to situations and what sort of people we are.)

What could you do to improve the communication? (See Section H: Asking Questions.)

How was Round 2 different from Round 1? Was it more satisfying? Were the reproductions more accurate?

Did asking questions encourage the speaker to become more specific and detailed in the information being volunteered?

Did you become more aware of the assumptions that you were making? How did you see beyond those?

Important Points to Cover:

We all have differing perceptions of things. Words conjure different images and meanings for different people in different contexts.

Conflicts often pivot on our different understandings of words. (E.g. What’s fair? What’s tidy? What’s complete?) Checking and rechecking with the other person can prevent and overcome confusion.

Becoming clear on what others mean when they speak is a wonderful empathy-builder.

Empathy Activities

Shopping List

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: Communication is enhanced when the listener plays an active role. (See Chapter 3. Empathy: Section G.) Time: 15 minutes Aim: To experience the effectiveness of questions in improving communication. |

Instructions: This activity will explore some of the ingredients of clear communication. There will be two rounds, with some discussion at the end of each round.

Divide the group into pairs, with Partners A and B.

Round 1

Partner A, think of five items that you would like partner B to buy. Arrange with Partner B as though B were about to go and buy them. (The trainer can suggest grocery items, office supplies, or whatever is appropriate to the group.)

Allow 2 minutes. Then, lead a large group discussion.

Discussion: Ask a few partners B what they are going to buy. Explore the details:

e.g. What size block of cheese?

What variety of milk – low fat, whole, skim, etc?

Does Person A have a particular greengrocer in mind?

Who is going to pay for it?

Do you need receipts?

Who did you consider was responsible for ensuring the communication was clear?

How successful would Partners B have been in making the purchases?

What can be done to ensure that Partners A receive exactly what they want?

Explore: Partners A could have volunteered more information.

Partners B could have asked more questions.

(See Empathy. Section H: Asking Questions.)

Instructions:Round 2

Ask partners to reverse roles. Ask the speaker to do as before or change the scenario e.g. arrange to go out to dinner. Place the emphasis on the listener asking questions to elicit information.

Allow 3 minutes.

Discussion: Was your communication more effective when listeners participated actively?

Did the speakers begin to volunteer more information?

Were there any difficulties in constructing appropriate questions?

Empathy Activities

Identifying Feelings and Responding

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: Active listening requires that we identify the feelings the speaker is expressing. Time: 10 minutes Aim: To practice identifying feelings and responding to them. Handout:“Identifying Feelings and Responding” |

Instructions: In this activity, we will complete a worksheet developing appropriate active listening responses.

Ask participants:

- to read each statement

- to identify the feeling being expressed

- to write an appropriate active listening response.

Discussion: Choose some examples and ask what participants have written. Ask if there are any that participants found difficult and consider these more closely.

Invite comments and insights.

Important Points to Cover:

Often a person’s underlying feeling is masked by anger or frustration at someone or something else.

Sometimes a person’s feeling is expressed as an action or as a description.

It can be difficult to be certain what feeling is being expressed, so we need to be cautious in our response, and show a willingness to be corrected – to have the person say “No, it’s not that. It’s…”

Empathy Activities

Active Listening to Affirm

Trainers’ Information OnlyContext: In a conflict situation, often people’s most important need is to sort out their own ideas and feelings. Finding someone who can act as a sounding board can help them to do this. (See Chapter 3. Empathy: Section I.) Time: 40 minutes Aim: To practice active listening in order to affirm the other person, and to acknowledge and explore a situation. |

Instructions: Listening to affirm is a skill which needs plenty of practice. Working with a partner, we will each have the opportunity to try our active listening skills.

Divide the group into pairs.

Round 1

Partners A, you choose a matter which is of concern to you. Choose something which has some degree of emotional importance to you, and about which you are willing to talk to partner B.

Partners B, you listen very attentively to Partner A, reflecting back the essence of what you hear. Rely mainly on paraphrasing and summarising what partner A says. Allow there to be some silences, and only probe with questions when the flow from partner A diminishes. Take care that your questions don’t lead away from Partner A’s main concerns.

Allow 10 minutes.

Pair Discussion: Ask partners to share with each other what they experienced.

- How did it feel to be listened to so attentively?

- What worked and what didn’t?

- What areas can be improved?

Round 2

Reverse activity: speaker becomes listener, listener becomes speaker. Allow ten minutes, followed by partner discussion, then entire group discussion.

Discussion: Did speakers say more than you thought you would? Why did that happen?

Did speakers feel heard? If so, what gave you that feeling?

Did listeners find yourself wanting to give advice, reassure, share your own experience? Were you able to refrain from doing so?

Were there spaces in the conversation? How did that feel? Did either person want to fill them in?

Behavioural Style Questionnaire

| Gives priority to detail and organisation

Sets exacting standards Approaches tasks and people with steadiness Enjoys research and analysis Prefers operating within guidelines Completes tasks thoroughly Focuses attention on immediate task Likes accuracy Makes decisions on thorough basis Values standard procedures highly Approaches work systematically Likes to plan for change

Total: |

…..

…. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. …..

___ ___ |

Gives priority to achieving results

Seeks challenges Approaches tasks and people with clear goals Is willing to confront Makes decisions easily Is keen to progress Feels a sense of urgency Acts with authority Likes to take the lead Enjoys solving problems Questions the status quo Takes action to bring about change

Total: |

…..

….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. …..

___ ___ |

|

Gives priority to supporting others Enjoys assisting others Approaches people and tasks with quiet and caution Has difficulty saying no Values co-operation over competition Eager to get on with others Willing to show loyalty Calms excited people Listens well/ attentively Prefers others to take the lead Gives priority to secure relationships and arrangements Prefers steady not sudden change

Total: |

….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. …..

___ ___ |

Gives priority to creating a friendly environment Likes an informal style Approaches people and tasks with energy Emphasises enjoying oneself Rates creativity highly Prefers broad approach to details Likes participating in groups Creates a motivational environment Acts on impulse Willing to express feelings Enjoys discussing possibilities Keen to promote change

Total: |

….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. …..

___ ___ |

This questionnaire is to be used as a guide only. It has not been validated. For an accurate behavioural style questionnaire we recommend completion of the full Personal Profile System, available from Inscape Publishing, Inc. or Integro Learning Company P/L, PO Box 6120, Frenchs Forest DC NSW 2086 Australia

.

DISC Model

People have a variety of preferred and habitual ways of behaving and responding, depending on the context. When communication is difficult, it can be helpful to tailor your approach to suit others’ preferences and habits.

Within any behavioural style, people can be both skilled at getting the job done and getting along with others.

Once aware of areas needing improvement, people can often develop new skills, to increase the flexibility of their behavioural repertoire.

Differences in Behavioural Style

| Who have you noticed using these behavioural styles?

Direct: Influencing: Stabilising: Conscientious: |

Think of someone with whom you often find yourself in conflict. What is the behavioural style you often notice them using?

How might knowing this help you to communicate, work more co-operatively, and be less judging of their behavioural style?

How could you modify your behaviour to address their needs better?

If you did modify your behaviour, how might their response be different?

Empathy Blockers

Communication Killers, Fouls!

|

Who does it? |

||||

| Self | Other | |||

| DOMINATION

|

Threatening: ”If you are not able to get to work on time we’ll have to review your job here?”, “Do it or else.” | |||

| Ordering: “I’ll see you immediately in my office.”, “Don’t ask me why, just do it because I said so.” | ||||

| Criticising: “You don’t work hard enough.”, “You’re always complaining.” | ||||

| Name-calling: ”Only an idiot would say that.”, “You stupid fool.” “You’re neurotic.” | ||||

| “Should’’ing or “Ought”ing: “You ought to face the facts.”, ”You shouldn’t be so angry.” | ||||

| MANIPULATION | Withholding Relevant Information: “If you knew more about this you would see it differently.” | |||

| Interrogating: ”How many hours did this take you?” ”How much did this cost?” Why are you so late?” ”What are you doing now?” | ||||

| Praising to Manipulate: “You’re so good at report writing, I’d like you to do this one.” | ||||

| DISEMPOWERMENT | Diagnosing Motives: ”You are very possessive.” “You’ve always had a problem with time management.” | |||

| Untimely Advice: “I don’t seem to be managing.” “If you’d just straighten up your desk you would not be in this panic.” ”Why didn’t you do it this way?” ”Just Ignore him.” | ||||

| Changing the Topic: “I’m worried about my son’s progress at school”. ”Yes it is a worry…Did I tell you that I’m applying for a new job?” | ||||

| Persuading with Logic: ”There’s nothing to be upset about. It’s all quite reasonable – we just… then we…”. | ||||

| Topping: “I smashed the car last week…… ” ”When I smashed my car…” | ||||

| DENIAL | Refusing to Address the Issue: ”There’s nothing to discuss. I can’t see any problems.” | |||

| Reassuring: ”Don’t be nervous.”, ”Don’t worry, it will work out.”, ”You’ll be fine.” | ||||

Create Empathy

Listen with your head and your heart.

Empathy is sensing another’s feelings and attitudes as if we had experienced them ourselves. It is our willingness to enter another’s world, and being able to communicate to that person our sensitivity to them. It is not blind sentimentality; it always retains some objectivity and distance. We do not lose our own identity, though we discover our common humanity.

Create empathy by:

taking seriously others’ needs and concerns

valuing feelings and attitudes

respecting others’ privacy, experience and values

listening actively

encouraging further elaboration and clarification

using open body language and a warm vocal tone

reserving judgement and blame

displaying interest in what others communicate

withholding unsought advice

supporting others’ attempts to find a solution

making affirming statements and gestures.

Identifying Feelings and Responding

Label the feeling in these statements, and give an appropriate response. Avoid parroting the speaker. Instead, active listen to paraphrase the statement. Your response may be a question. When you try to label other people’s feelings, you need a tentative, inquiring approach or have a question in your tone of voice.

Feeling

Example: I really hate him Anger

Response: You feel really angry with him?

Feeling

1. I’m not much good at anything

Response:

2. I can’t sense feelings like others can

Response:

3. I’m a lousy parent

Response:

4. I don’t know what to do

Response:

5. I’ve had nothing but trouble from this organisation

Response:

6. I can’t get along with them at all

Response:

7. I have difficulty meeting people

Response:

8. I’d looked forward to the holiday but it was pretty lonely

Response:

9. I just can’t cope

Response:

10. There never seems to be anyone to help me

Response:

11. I need some time to myself

Response:

12. People just don’t listen

Response:

Active Listening… Some Helpful Hints

|

Things to Try |

Things to Avoid |

| Put the focus of attention totally on the speaker.

Repeat conversationally and tentatively, in your words, your understanding of the speaker’s meaning. Feed back feelings, as well as content. (Probe, if appropriate e.g. ”How do you feel about that?” or “How did that affect you?“) Reflect back not only to show you understand, but also so the speaker can hear and understand his or her own meaning. Try again if your active listening statement is not well received. Be as accurate in the summary of the meaning as you can. Challenge powerlessness and hopelessness subtly (e.g. try “It is hopeless” instead of “It seems hopeless to you right now.” Try ”You can’t find anything that could fix it?” instead of “There’s nothing I can do”). Allow silences in the conversation. Notice body shifts and respond to them by waiting. Then, e.g. ”How does it all seem to you now?“ |

Avoid talking about yourself.

Reject introducing your own reactions or well intentioned comments. Try not to ignore feelings in the situation. Avoid advising, diagnosing, baiting, reassuring, encouraging or criticising. Dispense with thinking about what you will say next. Avoid parroting the speaker’s words or only saying “mm” or ”ah, hah”. Don’t pretend that you have understood if you haven’t. Avoid letting the speaker drift to less significant topics because you haven’t shown you’ve understood. Avoid fixing, changing, or improving what the speaker has said. Don’t change topics. Resist filling in every space with your talk. Don’t neglect the non-verbal content of the conversation. |

Active Listening for Different Purposes

| SKILLS

PURPOSES |

Non-verbal Skills | Following Skills | Reflecting Skills |

|

To Gain Information to find out the details of what another is saying.

to clarify instructions and to gain information.

|

Use appropriate body language – nodding, noting, recording, watching.

Focus your concentration, block out distractions. |

Ask many questions.

Write notes.

Use memory joggers. |

Confirm your understanding by repeating key points. |

|

To Give Affirmation to show empathy and give acknowledgement.

to help the speaker hear and understand his or her own meaning.

|

Choose a non-distracting and comfortable environment. Is privacy needed?

Remove inappropriate physical barriers e.g. large desk

Consider moving closer to the speaker.

Adopt an open, encouraging posture with welcoming gestures, and appropriate eye contact to show attention and involvement.

|

Use minimal verbal encouragers – such as ”mm” and ”ah hah”.

Ask only occasional questions.

Allow attentive silences. |

Reflect back both feelings and content.

Use your own words to feed back your understanding of the speaker’s meaning.

Summarise the major concerns.

Use a tone of voice that shows warmth and interest. |

|

To Respond To Inflammation to let the speaker know you’ve heard the complaint, the anger and/or the accusation.

to defuse the strong emotions.

|

Avoid defensive or aggressive posture and gestures.

Consider extra distance to make you feel safe.

Use attentive eye contact and an assertive stance.

|

Use obvious verbal indicators that you’ve understood – a clear ”yes”, a strong “OK”.

Ask questions to understand the basis of the attack. |

As for listening to affirm (above).

In reflecting back, try to put some heat in your voice (not a flat tone), gradually reducing it as the speaker ”cools” down. |

Listen

When I ask you to listen to me

and you start giving advice

you have not done what I asked.

When I ask you to listen to me

and you begin to tell me why I shouldn’t feel that way,

you are trampling on my feelings.

When I ask you to listen to me

and you feel you have to do something to solve my problems,

you have failed me, strange as that may seem.

Listen! All I ask is that you listen.

Not talk or do – just hear me.

Advice is cheap: 50 cents will get you both Dorothy Dix and

Dr Spock in the same newspaper.

And I can DO for myself ; I’m not helpless.

Maybe discouraged and faltering, but not helpless.

When you do something for me that I can and need to do

for myself, you contribute to my fear and weakness.

But when you accept as a simple fact that I do feel what I feel,

no matter how irrational, then I quit trying to convince

you and can get about the business of understanding what’s

behind this irrational feeling.

And when that’s clear, the answers are obvious and I don ‘t

need advice.

So, please listen and just hear me, and if you want to talk,

wait a minute for your turn; and I’ll listen to you.

Anonymous