Creative Response

Conflict Resolution Network

Objectives

Objectives:

- To understand how powerfully the messages we give ourselves affect the outcomes when faced with conflict.

- To explore ways of transforming our thought patterns.

Session Times:

1 ¾ hours: Sections A–E

1 hour:Sections B–D

½ hour: Abbreviate Sections B–D

Essential Background: Understanding Conflict

A.Stimulus Activity2.2

B.Exploring Our Responses to Conflict: React or Respond2.2

C.Two Models for Approaching Conflict: Perfection and Discovery2.4

D.Looking for the Positive in Conflict2.6

E.An Action Program for Developing More Creative Responses to Conflict2.7

Activities:

The Block PuzzleA.2.1

Handouts:

Section C:Perfection and Discovery ApproachesH.2.1

Creative Response

Ah, Conflict! What an Opportunity!

Stimulus Activity

(20 minutes)

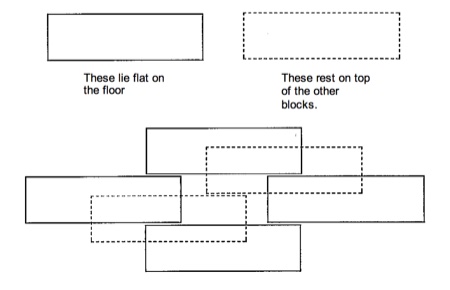

The Block Puzzle: working with six blocks, participants are given a small construction problem to explore the importance of mindchatter in affecting our ability to solve problems. (See Creative Response Activities, pg A 2.1.)

Exploring Our Responses to Conflict: React or Respond

(20 minutes)

Reflection: Think of an argument or a run-in that you had with someone recently. Feel it… remember it… Now let yourself know it will recur. Tomorrow, you’re going to have that same argument again.

Question: What are you feeling? What are you thinking?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- Dread

- Anxiety

- Fear

- Worry

- Exhilaration

- Excitement.

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- Nausea

- Butterflies

- Tightening of muscles around neck, jaw, shoulders.

Question:What thoughts are running through your mind?

Discussion: Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- I wish it would go away

- It’s too difficult

- Why is it happening again?

These messages that we give ourselves are known as mindchatter or self-talk.

Mindchatter, what we tell ourselves, affects how we respond to situations. This conversation with ourselves is continuous. When we’re under stress the chatter increases. Because it affects the way we act and how we see the world, changing our mindchatter will change our view of the world and our reactions.

Question:How do you think our mind chatter affects our ability to deal effectively with the conflict?

Discussion: Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- It may make it hard to be open-minded.

- It may cloud our judgement.

- It may make us defensive.

(Refer to the effect of self-talk on participants’ ability to do the Block Puzzle.)

Question:Why do we so often give ourselves such negative messages?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- We’ve learnt these responses from early childhood.

- We don’t know how to behave in response to the behaviour that the other person is using in conflict.

- We don’t know how to manage our own responses.

- It’s hard to see beyond the immediate discomfort, to some constructive outcome.

Because we give ourselves these negative messages, we often find ourselves with a knee jerk reaction to conflict. We are not acting by choice, but out of habit.

Write on the board:

REACT

We may withdraw, sulk, scream, punish them, get cranky. Learning new patterns of greeting conflict may give us the choice to behave In a different, more appropriate way.

Write on the board.

OR

RESPOND.

By responding we can explore the possibilities of the situation. For example, what can be done to make this different, to make it work for all of us?

Two Models for Approaching Conflict: Perfection and Discovery

(20 minutes)

(For expanded discussion, see Thomas F Crum The Magic of Conflict (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987) p11–120.)

Question: What are some of the causes of conflict?

Discussion: Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might explore:

- power battles

- defining territories

- difference of opinion or ideas

- clash of values.

Question:What is it about ”difference” that causes conflict? Why don’t we just accept differences, instead of tying ourselves up in knots?

Discussion:Draw out participants’ responses. In addition, you might consider:

- We like to be right.

- We feel threatened by difference.

- We think our way is best.

When we’re caught up with what’s right, with how things should or shouldn’t be chances are we’re measuring the situation against a yardstick of PERFECTION.

(Some groups may feel more comfortable with the word “perfectionism”. Encourage participants to use their own words to identify the models. (The concept, not the names in the model, is the important point)

| SAY | WRITE on the Board | |

| When we are driven by whether things are |

right or wrong | |

| it can lead to | judgements | |

| and an | unwillingness to risk. | |

| What if it doesn’t work out? We may be left with a feeling of |

anxiety | |

| When we’re working on this basis we look for |

winners and losers | |

| and end up with | FRUSTRATION. |

Another way of measuring a situation is against a yardstick of DISCOVERY.

| SAY | WRITE on the Board | |

| Approach the situation with an attitude of |

inquiry and creativity. | |

| “That’s interesting, why did that happen?” This leads to |

acceptance | |

| and an | willingness to risk. | |

| and to try again. “I wonder what else I can do now?”, “How can I make it better?” We have a feeling of |

excitement | |

| Using this yardstick there are no winners and losers, only |

learners | |

| and | FASCINATION. |

Using a discovery approach we can still aim for excellence.

Discovery doesn’t mean settling for second best, or grinning and bearing it. It means acknowledging how we feel about a situation and looking for what we can learn, for the new doors that are opening and for the ways that we can make it different in the future. Excellence becomes the path itself rather than the destination. Allowing mistakes and being willing to risk is more likely to achieve excellence than a model of perfection which is limited by a definition of what’s right.

Give out the handout: “Perfection and Discovery Approaches.”

Reflection:Ask participants to think again of the conflicts they recalled earlier in the session. What could be discovered in these? What could be learnt?

Looking for the Positive in Conflict

(20 minutes)

We’ve already talked about mindchatter. The negative messages we give ourselves can inhibit our ability to do things. With the block puzzle, the statement ”I’m no good at these things,” made it almost impossible to succeed. That type of negative message sets us up for failure and frustration.

Look for the positive side of the situation, for the opportunity. The language we use is very powerful in directing our thoughts and ultimately the outcome in a situation.

Reframe our negative “I can’t do this” to “I need to work out a plan” or “I need to learn these skills”.

Think of a new way of seeing a situation. A two year old child can be seen as going through the ”terrible twos” or going through the ”champagne year”. The new colleague at work can be ”making lots of mistakes” or ”willing to have a go”.

Group Activity:Creating positive statements about conflict: participants construct statements to focus their attention on the opportunity in the conflict. (See below for details.)(5 minutes)

Ask participants to reflect again on the conflicts they identified earlier. (See Part B.)

Write down a positive message you can give yourself about that particular conflict.

Allow 2–3 minutes.

Now try to invent a positive statement which you could use to approach conflict in general.

e.g. ”Celebrate successes, learn from failures”.

“l’m here to solve problems”.

“Here’s a challenge!”

Write the group’s creative responses on the board and, if possible, prepare them as a handout for the next session.

Conflict is a chance to move on, to have things change, to enter richer relationships.

The positive messages we’ve just composed are a powerful antidote to the negativity that we sometimes feel towards conflict. Another powerful message is:

Write on the board:

AH, CONFLICT!

WHAT AN OPPORTUNITY!

Greet conflict with an attitude of discovery.

An Action Program for Developing More Creative Responses to Conflict

(20 minutes)

Creative response is about turning problems into challenges. The four steps are:

Write on the board:

- Choose to respond

- Accept what is

- Ask “What can I learn here?”

- Look for the opportunity

Some helpful strategies to achieve this can be:

- Set a specific time each week to initiate action, letters, phone calls and conversations. Don’t wait for others to take the first step. If it’s a “tough one” the other person will probably avoid it.

- Focus all our attention and energy on the achievement of the objectives we have set.

- Use encouraging, affirmative language in our mindchatter and when we talk to others about difficulties. For example, I’ve decided to” in place of “I have to”. Acknowledge the problem, be positive about the outcome.

- Learn how to relax mentally and physically using meditation and other mind relaxing techniques.

Group Activity:A More Creative Response to a Conflict: participants, working in pairs, consider a current unresolved conflict to develop a plan for a more creative response. (See below for details.) (10 minutes)

Ask the group to divide into pairs.

Think of a current unresolved conflict in your life. Partner A, describe this conflict to Partner B. Then, through discussion, try to explore each of the four steps listed on the board.

Allow 5 minutes.

Now, Partner B, describe a conflict to Partner A and, again through discussion, explore the four steps for developing a more creative response to conflict.

Discussion: Encourage questions and comments from participants.

Final Comments:Looking for the opportunity in conflict helps us to shift from fixed positions, and to consider a broader range of options. This means that the solution upon which we settle is more likely to reflect more of the needs and concerns of those involved, and address the major issues at stake more effectively.

Creative Response Activities

|

Trainers Information Only Context: The negative messages we give ourselves often inhibit our ability to deal with conflict. As well, locking into the idea of the right solution can blind us to other options. (See Chapter 2: Creative Response: Section A.) Time: 20 minutes Aim: To experience the effect of mindchatter and concern for the right solution on one’s problem solving ability. Requirements: A set of six blocks for each participant. Each set can be different, but within sets, the blocks must be the same shape and size e.g. children’s building blocks Cuisenaire rods video boxes matchboxes paperback books. |

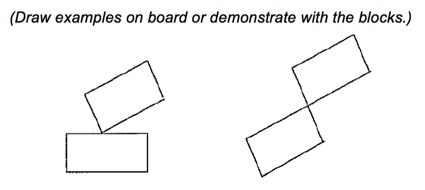

Instructions:We’re going to do a puzzle to look at what might enhance or inhibit our problem-solving ability.

You have 3 minutes to solve this puzzle.

Arrange the six blocks so that each touches exactly three others, no more and no less.

Touching means that the whole or part of a flat surface of the blocks must meet.

Contact through an edge or corner does not count. e.g. These do not count!

You can sit on the floor, or use your chair, or your folder as a stable working surface.

Your time starts now.

At the end of 3 minutes, tell participants that their time is up.

Ask if anyone finished the puzzle. “Are you sure each of the blocks is touching three others?”…

Acknowledge those who finished, and those who didn’t.

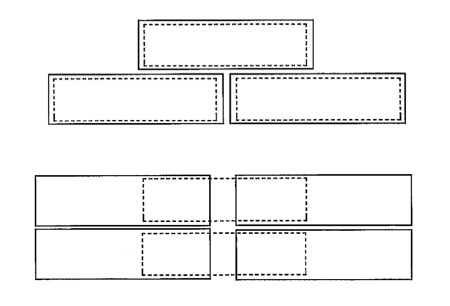

Show them a few sample solutions.

Three Sample Solutions:

Discussion:How did you feel when I asked you to do this exercise? What sort of thoughts ran through your mind? (After participants have responded, you might add: I’m no good at this; I can never do these things; Good, I really like these; I know I can do it; I’ve seen it done before etc.)

These messages that we give ourselves are known as mindchatter or self-talk.

Do you think your mindchatter affected your ability to do the puzzle?

For those of you who had negative mindchatter, do you think you would have approached the puzzle differently, if your mindchatter had been more positive?

What are some of the positive things you could have said to yourself? (After participants have responded, you might add: I haven’t played with blocks for years – this’ll be fun; Here’s a challenge; I wonder if I’ll be better at this sort of thing now than I was years ago?)

Who was concerned with getting it right? Did you assume there was only one right solution? Did looking for that right solution inhibit your efforts?

How did you go about solving the puzzle? What did you notice about the process you used? (This may be difficult to work out if you were looking for the right solution instead of noticing the process. Paradoxically, noticing the process may have propelled us to a solution.)

Was it:

- Random?

- Trial and error?

- Logical – think through before starting?

- Dividing up and tackling one part after another?

- Modifying some previous experience of similar puzzle?

Did anyone feel blocked in their efforts because of being locked into one pattern? (After participants have responded, you might add: only thinking of two dimensional rather than three dimensional solutions.)

Important Points to Cover:

Mindchatter affects our ability to solve problems, as does our pre-occupation with the right solution can inhibit our thinking. We may not realise that there are other ways of approaching a solution, nor that there may be more than one solution. The lateral thinking required to solve problems such as these is often the skill that is needed to solve a thorny conflict: a highly creative approach.

(Note: This exercise is taken from Edward de Bono The Five Day Course in Thinking (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968.))

Perfection and Discovery Approaches

When how we perceive ourselves and others…

|

… is judged against PERFECTION, we are driven by right/wrong judgements failures unwillingness to risk anxiety FRUSTRATION |

… is open to DISCOVERY, we are motivated by inquiry/creativity acceptance learning willingness to risk excitement FASCINATION |

Does a discovery approach close off the search for excellence? Not at all! We start by acknowledging how we feel about a situation and then look for what we can learn, for better ways of doing things, for new doors that are opening in the future. Being willing to risk is more likely to achieve excellence than a model of perfection which is limited by a definition of what’s right and how people ought to be.

Adapted from Thomas Crum The Magic of Conflict (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1987)