9 Conflict Resolution Skill Development (New for 2018)

Valerie Ubbes

Historical Background

Fifteen years ago, three professional organizations collaborated on a project to establish a Conflict Resolution Institute for Health Educators, Early Childhood Educators, and Middle Childhood Educators in Higher Education. In the first year, the Institute included a two-day training and a one-day follow-up training in Columbus, Ohio. The goal of the conflict resolution project was to provide education, training, and resources to university faculty in order to support the integration of conflict resolution content and skills into professional preparation programs. By the second year, the Institute expanded the training format and changed the program name to the Conflict Resolution Institute for Education Faculty in Ohio Colleges and Universities. Key leaders from the American Association for Health Education, the Conflict Resolution Education Network (CREnet), and the Ohio Commission on Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management (OCDRCM) worked together to establish the two-year institute to ensure safe and sustainable teaching-learning environments and to enable community conflicts to be handled efficiently and effectively without psychological or physical violence. This initiative, and the state-wide Ohio School Conflict Management Grant Trainings, served as a basis for the development of the national Conflict Resolution Education in Teacher Education (CRETE) project in 2003.

Goal of the Chapter

This chapter highlights some of the main learning outcomes of the Institute and then discusses how current health education faculty, including those implementing new public health programs, can think about and implement conflict resolution skills and concepts in an undergraduate curriculum for health education specialists.

Conflict Resolution Institute Objectives

The Conflict Resolution Institute focused on offering professional development modules to university faculty who were responsible for teaching teachers how to implement conflict resolution skills and concepts into Ohio preK-12 school curricula. The training modules included a customization of the Conflict Resolution Manual for Educators (Koch, 1995) aimed at institutionalizing conflict resolution programs on college campuses and querying faculty how they planned to implement their new knowledges and skills in the form of university action plans prior to year two of the training. During year 2 of the institute, the lead trainer facilitated and helped to refine personal skill development of faculty through conflict resolution role plays and activities. At the end of the second institute, the planning team developed a collection of lesson plans and revised action plans from participating faculty which allowed AAHE and CREnet to disseminate conflict resolution lessons to health education faculty nationwide. Follow-up communication with the Ohio Commission was instrumental in linking university faculty with state and local initiatives for conflict resolution.

A planning outcome of the Conflict Resolution Institute was a checklist of conflict resolution skills and concepts. Faculty received and practiced the list below, followed by a rubric that faculty used to self-assess their skill level and provide feedback to the facilitators during the institute training.

Concepts and Skills Practiced by Faculty at the Conflict Resolution Institute

- Acknowledge other people’s feelings with empathy

- Acknowledge another person’s perspective even if it is contrary to your own personal perspective

- Analyze and understand conflict that another person expresses

- Choose strategic, instead of reactive responses to conflict

- Commit to developing your conflict resolution skills through practice

- Develop multiple options for resolution of a personal conflict

- Develop a win-win solution that meets multiple interests

- Evaluate the positive and negative consequences of different options when resolving a conflict

- Express a range of feelings appropriately to others

- Identify some of the underlying issues in a personal conflictIdentify factors and feelings that escalate conflict between two or more people

- Identify healthy ways to tame intense feelings

- Identify personal interests that underlie positions

- Identify shared, differing, and opposing interests

- Identify your personal attitude toward negotiation (to win or to achieve fair outcome)

- Recognize differences between the fight or flight responses and a thoughtful avoidance

- Recognize different negotiation strategies in conflict resolution

- Recognize different response styles in conflict resolution

- Recognize cultural differences in body language and communication

- Understand a variety of human psychological needs

- Understand your own personal response to conflict situations

- Use active listening skills

- Use effective body language when in a conflict situation

- Use I-statements, re-framing, and summarization

- Use non-inflammatory language when in a personal conflict

The template below shows an assessment rubric for measuring competencies for different conflict resolution skills. Faculty who attended the institute reported an objective self-assessment score for different conflict resolution skills from the list above. Scores were averaged to help trainers make decisions on the amount of time to spend on each skill during the Institute.

Self-Assessment Template to Determine Faculty Training Needs on Conflict Resolution Skills

| 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | |

| Conflict Resolution Skill: ___________Choose from list above. | I need to start from scratch on this skill. | I could use more training (practice) on this skill. | I could learn something new about this skill during the training, but then let’s move on. | I’ve been there, done that, and know how to do that skill. I don’t need to be trained on it again. |

Note: Continuum adapted from Nancy Hudson, SCASS Health Education Assessment Project, Washington, DC

Curriculum Standards for PreK-Grade 12 Health Education and Beyond

Five years after the first Ohio Conflict Resolution Institute, there was a continuing interested in how health education teachers in public schools would be able to teach personal and social skills to children and youth on a national scope. Fifteen health educators formed a national revisions panel to review the 1995 National Health Education Standards (National Health Education Standards Committee, 2007) which addressed the following question prompt for curriculum: What should students “know” and “be able to do” as result of health instruction across the developmental lifespan? In the second edition of the National Health Education Standards (2007), communication was a key skill outlined in Standard 4 using the following rationale:

Effective communication enhances personal, family, and community health. This standard focuses on how responsible individuals use verbal and nonverbal skills to develop and maintain healthy personal relationships. The ability to organize and to convey information and feelings is the basis for strengthening interpersonal interactions and reducing or avoiding conflict.

The following list of performance indicators outlines a developmental sequence of skills that students should know and be able to do for communication and conflict resolution. Educators can use the performance indicators to design instructional lessons for children and youth from preschool to grade 12. However, there is also the possibility to extend these performance indicators in university classes for college students with the assumption that health education is still not adequately taught in American schools. Research has found that most children, youth, and young adults have not had adequate practice time in health education (CDC, 2015).

Of the eight National Health Education Standards, Standard 4 is the best choice for the teaching of communication and conflict resolution skills. Faculty who teach teacher candidates who will then go on to teach children and youth should advance these developmentally appropriate skills that are organized by grade-level performance indicators. As shown below, the focus should be on planning health lessons that will afford pre-professionals and their own students practice time to learn interpersonal communication skills, including conflict management and conflict resolution strategies, related to health issues and risks.

Standard 4: Students will demonstrate the ability to use interpersonal communication skills to enhance health and avoid or reduce health risks.

Performance Indicators

Pre-K-Grade 2

4.2.1 Demonstrate healthy ways to express needs, wants, and feelings.

4.2.2 Demonstrate listening skills to enhance health.

4.2.3 Demonstrate ways to respond in an unwanted, threatening, or dangerous situation.

4.2.4 Demonstrate ways to tell a trusted adult if threatened or harmed.

Grades 3-5

4.5.1 Demonstrate effective verbal and nonverbal communication skills to enhance health.

4.5.2 Demonstrate refusal skills that avoid or reduce health risks.

4.5.3 Demonstrate nonviolent strategies to manage or resolve conflict.

4.5.4 Demonstrate how to ask for assistance to enhance personal health.

Grades 6-8

4.8.1 Apply effective verbal and nonverbal communication skills to enhance health.

4.8.2 Demonstrate refusal and negotiation skills that avoid or reduce health risks.

4.8.3 Demonstrate effective conflict management or resolution strategies.

4.8.4 Demonstrate how to ask for assistance to enhance the health of self and others.

Grades 9-12

4.12.1 Use skills for communicating effectively with family, peers, and others to enhance health.

4.12.2 Demonstrate refusal, negotiation, and collaboration skills to enhance health and avoid or reduce health risks.

4.12.3 Demonstrate strategies to prevent, manage, or resolve interpersonal conflicts without harming self or others.

4.12.4 Demonstrate how to ask for and offer assistance to enhance the health of self and others.

The list of performance indicators articulate what students should know or be able to do within the following grade spans: Pre-K–Grade 2; Grade 3–5; Grade 6–8; and Grade 9-12. The performance indicators provide teachers a blueprint for organizing student assessment.

According to the 2016 School Health Policy and Practices Study (SHPPS), 71.8 percent of elementary schools, 84.3 percent of middle schools, and 90.2 percent of high schools report “using interpersonal communication skills to enhance health and avoid or reduce health risks” (p. 11). And the SHPPS Report also shows that just over 78 percent of districts have provided funding for professional development on classroom management techniques (e.g., social skills training, environmental modification, conflict resolution and mediation, or behavior management) to those who teach health education (p. 14).

Health Education Career Development

Students who graduate from high school can be encouraged to pursue a degree in health education. First-year college students across the country can choose from a variety of undergraduate majors, including health education, health promotion, health behavior, and health science. As of January 2015, universities were granted permission by the Council on Education of Public Health (CEPH) to offer an undergraduate program in public health. Prior to this date, the masters of public health (MPH) degree was considered the entry-level step for public health. Because Miami University (Oxford, OH) did not have an MPH graduate program, faculty felt that an undergraduate degree in Public Health would be advantageous. Miami University has had a history of different program names at the undergraduate level, including a Health Education program (1992 to 2015), a Health Appraisal and Enhancement program (1990 to 2012), a Health Promotion program (2012 to 2015), and currently a Public Health program (2015 to present). The new Bachelor of Science degree in Public Health is taught in the Department of Kinesiology and Health within the College of Education, Health, and Society.

The remainder of this chapter will explain one of the new courses in the Public Health undergraduate major called KNH 262 Public Health Education. The goal is to outline our process for implementing conflict resolution skill development in our public health major so other Ohio universities could benefit from our planning and course development. The information in the next section will show how the course is aligned to the national CEPH curriculum standards then outline the ways in which conflict resolution can be taught as a key curriculum skill in coursework that prepares students to sit for the certified health education specialists (CHES) credential.

Curriculum Standards for Undergraduate Public Health Programs

The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) requires that courses in a new undergraduate public health program will be aligned to at least one of these curriculum standards below:

1. The history and philosophy of public health as well as its core values, concepts and functions across the globe and in society;

2. The basic concepts, methods and tools of public health data collection, use and analysis, and why evidence-based approaches are an essential part of public health practice.

3. The concepts of population health, and the basic processes, approaches, and interventions that identify and address the major health-related needs and concerns of populations.

4. The underlying science of human health and disease including opportunities for promoting and protecting health across the life course.

5. The socioeconomic, behavioral, biological, environmental and other factors that impact human health and contribute to health disparities.

6. The fundamental concepts and features of project implementation, including planning, assessment, and evaluation.

7. The fundamental characteristics and organizational structures of the U.S. health system as well as the differences in systems in other countries.

8. The basic concepts of legal, ethical, economic and regulatory dimensions of health care and public health policy and the roles, influences and responsibilities of the different agencies and branches of government.

9. The basic concepts of public health-specific communication, including technical and professional writing, and the use of mass media and electronic technology.

In their sophomore year, Miami University students take the course entitled KNH 262 Public Health Education for their public health major and for the development of competencies that lead to the Certified Health Education Specialist exam upon graduation. The basic outline of the course is shown below:

| KNH 262 | Public Health Education |

| Course Description | Foundational principles and techniques of health education pedagogy including professional assessments preparing for the Certified Health Education Specialists credential. |

| Credit Hours | 3 |

| Prerequisites | None |

| Instructor | Valerie A. Ubbes, PhD, MCHES |

| CEPH Standards that will be addressed: | The assignments for this course are aligned to the following curriculum standards from CEPH (Council on Education of Public Health): 1. The history and philosophy of public health education as well as its core values, concepts and functions across the globe and in society. 2. The basic concepts, methods and tools of public health education data collection, use and analysis, and why evidence-based pedagogical approaches are an essential part of public health education practice. |

| Learning Outcomes | Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to: 1. Differentiate between public health and public health education approaches for individuals and small groups who voluntarily choose to improve their health behaviors and habits in a variety of health education and health care settings; 2. Plan and apply the nine evidence-based instructional strategies (pedagogy) that are known to improve learning across all age groups and different disciplines; 3. Complete a professional assessment matrix to determine perceived competence and practical experiences in the Certified Health Education Specialist (CHES) credential. |

| Required Textbooks | Connolly, M. (2012). Skill-based health education. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett. National Commission for Health EducationCredentialing, Inc. (2010). The health education specialist: A companion guide for professional excellence (6th Edition). Whitehall, PA. |

| Weekly Schedule | Week 1 Introduction and Philosophy of Health Education Developing Your Professional Philosophy, Principles, and Pedagogical Practices Week 2 Inquiry-Based Pedagogical Models: Service Learning, Problem Based Learning, Cooperative Learning, and Project Based Learning Curriculum and Instruction in Health Education: School and Non-School Settings Week 3 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Department of Adolescent & School Health National Health Education Standards 1, 2, 3, and 8 Week 4 Habits of Health and Habits of Mind Model© for Skill-Based Health Education National Health Education Standards 4, 5, 6, and 7 Week 5 Community Health Education Philosophy, Principles, and Pedagogical Practices Week 6 Clinical Health Education Philosophy, Principles, and Pedagogical Practices Week 7 Implementation of Demonstration Projects: Putting Evidence-Based Instructional Strategies into Action Week 8 CHES Competency 1: Assess Needs, Assets, and Capacity for Health Education Week 9 CHES Competency 2: Plan Health Education Week 10 CHES Competency 3: Implement Health Education Week 11 CHES Competency 4: Conduct Evaluation and Research Related to Health Education Week 12 CHES Competency 5: Administer and Manage Health Education Week 13 CHES Competency 6: Serve as a Health Education Resource Person Week 14 CHES Competency 7: Communicate and Advocate for Health and Health Education |

As you see above, the seventh competency for the health education specialist (CHES) certification involves “communicate, promote, and advocate for health, health education/promotion, and the profession”. For a full list of the competencies and sub-competencies that students practice in course assignments, see here:

https://www.nchec.org/assets/2251/hespa_competencies.pdf

By looking only at the certification skill of communication, we see that public health students who wish to gain a certification as a health education specialist should “know” and “be able to do” the following competencies:

Area VII: Communicate, Promote, and Advocate for Health, Health Education/Promotion, and the Profession

7.1. Identify, develop, and deliver messages using a variety of communication strategies, methods, and techniques

7.1.1. Create messages using communication theories and/or models

7.1.2. Identify level of literacy of intended audience

7.1.3. Tailor messages for intended audience

7.1.4. Pilot test messages and delivery methods

7.1.5. Revise messages based on pilot feedback

7.1.6. Assess and select methods and technologies used to deliver messages

7.1.7. Deliver messages using media and communication strategies

7.1.8. Evaluate the impact of the delivered messages

Although the above list does not address conflict resolution directly, the plan is to demonstrate multiple pedagogical approaches when “educating for health” (e.g., cooperative learning, service learning) and to implement conflict resolution skill practice throughout the course. For example, a more advanced list of conflict resolution skills is shared below. Since the author was both on the planning team for the original Conflict Resolution Institute in Ohio and on the National Health Education Revision Standards committee, a key question includes: What are conflict resolution skills that college students may need to “know” and “be able to do” as a professional in public health education? Some key conflict resolution skills include:

- How to respond verbally to a stressful conflict situation without shouting.

- How to respond to a stressful situation without using derogatory body language.

- How to de-escalate conflict without taking sides.

- How to stay calm when someone calls you a bad name.

- How to express remorse without touching a person.

- How to step away from an unreasonable demand.

- How to take time for quiet after making it through conflict.

- How to regulate emotions in different conflict situations.

- How to establish ground rules for work or community-based meetings.

- How to listen to others by hearing words and seeing facial expressions.

- How to redirect a meeting when one person talks all the time.

- How to establish a climate for “thinking before speaking”.

- How to stop ruminating and reliving situations again and again.

- How to establish personal communication boundaries for body parts, e.g., tongue, fists, feet, lips, elbows.

- How to manage conflict during a heated discussion that erupts into name calling.

- How to be heard when no one is listening.

- How to turn 180 degrees from loud to quiet when involved in a heated conflict.

- How to align thinking, feelings, and actions toward peace when responding to daily challenges.

- How to acknowledge another point of view with a nod, smile, or eye contact to demonstrate that the words were received.

- How to remain seated in conflict by putting hands under legs and breathing deeply rather than speaking.

- How to reach a difficult agreement with a handshake.

- How to stay calm when someone makes an aggressive expectation of you without warning.

- How to deal with frustration when you feel out of the communication loop and have little background knowledge in an argument.

- How to say no to a colleague in an agreeable way.

- How to redirect a public conversation that is fraught with gossip and rumors.

- How to negotiate a win-win situation that is spiraling toward negative outcomes.

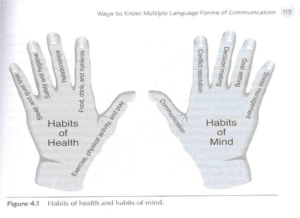

A key model that organizes personal and professional development in the undergraduate Public Health Education course is called Habits of Health and Habits of Mind (Ubbes, 2008, p. 113). As shown below, the Habits of Health model (left hand) outlines the health behaviors to be practiced every day. The Habits of Mind model (right hand) shows the cognitive skills that lead to the doing of the health behavior. For example, the cognitive skills of communication and conflict resolution are practiced daily when building the health behavior of relationships. Health educators, medical and dental professionals, and therapists can all benefit from early and ongoing training in communication and conflict resolution skill development leading to effective interpersonal relationships with their learners, participants, and clients. This model uses a developmental perspective across the lifespan to help people practice daily habits and routines for health. When the Habits of Health and the Habits of Mind are integrated and combined on a daily basis, it forms the whole curriculum for the whole person.

In conclusion, a brief historical review of the Ohio Conflict Resolution Institute highlighted the concepts and skills for faculty to learn and take back to students in their university classrooms across all disciplines and majors. Health education curriculum standards were shared to advance the skill development of communication and conflict resolution in grades preK-grade 12. Curriculum standards from the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) were outlined via a new undergraduate course at Miami University called Public Health Education, which contains a communication competency for the Health Education Specialist certification (CHES). Because the CHES competency does not address conflict resolution skill development specifically, a list of subskills were included. Finally, the Habits of Health and Habits of Mind model (Ubbes, 2008) was shared as a visual textual model for planning interventions in health education. The skills of communication and conflict resolution are highlighted as Habits of Mind to be practiced daily across a variety of health behaviors (Habits of Health) with a focus on building quality relationships.

Footnote

Personnel for the Conflict Resolution Institute included: Jennifer C. Batton, Ohio Commission for Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management, Columbus, OH; Randall R. Cottrell, EdD, MCHES, University of Cincinnati; Susan Koch, PhD, Northern Iowa University; Heather Prichard, CRENET; Becky Smith, PhD, American Association for Health Education, Reston, VA; Valerie A. Ubbes, PhD, MCHES, Miami University, Oxford, OH; and Terrance Wheeler, PhD, JD, Capital University.

References

Joint Committee for National Health Education Revisions Panel. (2007). National Health Education Standards. Accessed on November 17, 2017 at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/standards/index.htm

Koch, S. (1995). Conflict resolution manual for educators. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Ubbes, V.A. (2008). Educating for health: An inquiry-based approach to preK-8 pedagogy. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). School health policies and practices study. Accessed on November 17, 2017 at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/results.htm

About the Author: Valerie A. Ubbes, PhD, MCHES, Associate Professor, Public Health, Miami University, Oxford, OH, ubbesva@miamioh.edu