11 Organizing Principles in Peace and Conflict Studies (New for 2018)

David Derezotes

Introduction

The Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) program at the University of Utah (UU) is an undergraduate program in the College of Humanities that offers both a major and minor degree. Now roughly eight years old, the program has doubled in size over the past three years. Many students have double majors, with such disciplines as Medicine, Law, Political Science, and International Studies. The PCS program now has three required classes, and students have the freedom to choose the bulk of their classes from a menu of approved classes across campus.

In this chapter, four principles in teaching Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) are presented. Students and faculty find these interrelated approaches useful in developing curriculum and teaching in PCS. The first has implications for what is taught in the curriculum, the second and third help organize how we think about peace and conflict issues, and the fourth frames how the curriculum is taught. Consciousness work is the heart of the program; we challenge ourselves and our students to see the world (including one’s inner world) the way it is and to accept that world as it is. Systems theory, incorporates the micro, mezzo, and macro levels of analysis, so we can see how each individual is interconnected with everything around us. The ecobiopsychosocialspiritual perspective addresses the many interrelated ways a human being develops across the lifespan. Finally, experiential learning, learning by doing, provides an opportunity for students to have direct experiences in peace and conflict work, both in and outside the classroom.

The challenge of teaching PCS in a time of global ressentiment

Many people state they are “for peace”. In the early development of a Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) program, there were many volunteers to help form a planning committee and write proposals. Students were attracted to the program, some because their wonderful idealism, and some because the interdisciplinary choices make it relatively easy to for them get a quick minor.

One of my students said recently, “It seems like everyone is angry with everybody”. This same observation appeared in the literature from Indian scholar J. Mishra (2017) who has called this time a global “Age of Anger” characterized by an “…existential resentment of other people’s being, caused by an intense mix of envy and sense of humiliation and powerlessness, ressentiment, as it lingers and deepens, poisons civil society and undermines political liberty, and is presently making for a global turn to authoritarianism and toxic forms of chauvinism” (Mishra (2017, p. 14). This universal anger or ressentiment can be analyzed from a systems perspective and an ecobiopsychosocial perspective, using experiential exercises that support students’ consciousness work.

Consciousness work

Consciousness may be defined as reverent awareness; which is both seeing things as they are and being okay with the way those things are. Many PCS students initially struggle with this definition, because they refuse to accept a world that is so full of violence and conflict and worry that consciousness implies that there is nothing they can do to be of service to that suffering world. In fact, the opposite is true. The PCS helps students see how their consciousness can in fact have the most profound effect in developing inclusive communities and promoting social justice, in part because it fosters the kinds of relationships that can bridge differences and build inclusive communities.

This idea that consciousness is essential to social transformation can be found in most of the world’s wisdom traditions. Students seem to respond well to the words and works of J. Krishnamurti, for example, who was arguably one of the clearest voices speaking about peace and violence in the 20th Century. The PCS program offers these basic ideas to students, partially based upon Krishnamurti’s (e.g., 1996) work:

- Each one of us is response-able for (and able to respond to) the violence in the world

- Violence and conflict often originate from the desire to change something in the world, including the desire to change myself, in part because the only thing I can change in the here-and-now moment are my own attitudes and actions.

- Instead of trying to change myself or the world, I can use consciousness to accurately see and accept the ways things are. As I become conscious of my own inner conflicts and tendency towards violence, my conflicts and violence no longer have the same power to control me.

- When I approach people with an attitude of consciousness, the other person is more likely to respond in a positive way. Consciousness is helpful in the dialogue process, which is described later in this chapter; these ground rules help people bridge the differences that divide us.

Each student is encouraged to do their own inner work, including “owning” her or his own hidden biases, projections, emotional triggers, identifications, and traits of ressentiment. The PCS program teaches that the word “healing” has a Latin root that means “to become whole”, so that as we observe what is hidden inside of us, those shadow traits become seen and no longer have power over our attitudes and behaviors.

Hidden biases are unconscious (shadow) beliefs that can be made conscious, such as a belief that “Green” people are more intelligent and friendly than “Purple” people. Projections are shadow qualities inside me that I am not yet ready to see, so I only see them in others, such as the man who refuses to see his same-sex attraction, so he harasses other men whom he perceives as gay. Emotional triggers are situations and interactions that tend to bring up intense reactions of sadness, anger, fear, and other difficult emotions, such as with a person who immediately gets intensely angry whenever anyone suggests that s/he is too intense. Identifications are mechanisms where the individual not only has a strong belief, but moves to a place where “the belief is now him” and “he is the belief”. Identifications make violence possible, when for example; a person is willing to go to war when anyone criticizes the religion he identifies with. Finally, ressentiment, which we defined above, may include such traits as insensitivity to other people’s suffering, an underlying desire for revenge, and a tendency to react with anger when under any kind of stress.

Through the PCS program, students are challenged to do consciousness work by integrating such work into their assignments. Classes always include journaling assignments through which students reflect on their emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual responses (see section on lifelong development below) to the class. The journals are kept confidential, and the instructor responds to each student’s journaling.

Another assignment that encourages consciousness work uses reading reflections. PCS find that many students are reluctant to read textbooks, and that assignments that are linked to readings encourage them to open up these books, and check out other resources. Instead of only asking students to do the traditional “critical thinking”, we ask them to do “conscious thinking and feeling”. Conscious thinking and feeling simply means that students look at themselves honestly and accept who they are in each moment. Thus, in their reading reflections, students choose readings, write a report on what they read, and also report on their conscious thinking and feeling responses.

Systems perspective: Integrating macro and micro perspectives

PCS find it useful to understand peace and conflict from an integrated perspective that always includes analysis on the micro, mezzo, and macro levels of human interaction. The micro level can be thought of as personal relationships, such as most people have in their home, school, or work environment. The macro includes systems such as cities, states, and countries and the policies that govern them. The mezzo is in the middle, and represents small and large groups where people come together, such as neighborhood associations, book clubs, and local political organizations. Students are introduced to this systematic way of assessment and intervention in the Introduction to PCS class, and the concepts are reinforced in thefinal Integrative Seminar

Ressentiment can be analyzed from a systems perspective. On the macro level, as Mishra (2017) writes about, there are for example many people around the world who are exposed through mass media and communications technology to promises of wealth and power, yet they increasingly feel that they are do not have equal access to wealth and power. On the mezzo level, individuals may be influenced towards ressentiment by the statements they hear from others for example in the work environment, at their church, or in their exercise club. On the micro level, we know that not everyone is impacted in the same way by these macro and mezzo factors, so students could study what qualities in the individual make someone resilient towards ressentiment.

Case example: Incorporating the micro, mezzo, and macro levels

In the Introduction to PCS class, one of the students brings up a case that she would like to discuss with her classmates and teachers. She is doing an internship with a wilderness advocacy group that is engaged in a conflict about the leasing of federal lands for oil and gas exploration. On one “side” there are the oil and gas companies who seek permission to exploit oil and gas reserves as well as a collection of local and state politicians and others leaders who support this exploitation. On the other “side” there is a collection of conservation nonprofit organizations as well as American Indians representing a local tribe who live adjacent to the federal lands.

The instructor writes the terms ”MICRO”, “MEZZO”, and “MACRO” across the whiteboard and asks the students to analyze the conflict from all three perspectives. As the students suggest areas of analysis that fit under the three headings, she writes them on the board.

The students first talk about the micro level , and suggest that there are many personal relationships between local people, where friends, co-workers, neighbors, and family members may disagree strongly about what should happen with this oil and gas leasing conflict.

On the mezzo level, the students talk about how different local groups and organizations are in conflict with each other over the leasing proposals. These might include local institutions, like churches, schools, clubs, and work locations where people who know each other may have very different views about the oil and gas leasing conflict. On the macro level, students study the local, state, and national policies that help guide how large-scale political and economic systems work.

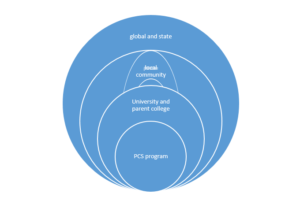

Situating the Peace and Conflict Studies program

Another way to teach about the systems perspective is to look at the PCS program and how it is situated in various systems. Each PCS program lives in a context of community and campus locations. Some PCS programs are developed in reaction to the power or perceived power of majority political, religious, and cultural populations found in state, regional local, and campus communities (see Figure 1 below). For example, on the one hand, the UUprogram is in a “red” state with a majority religion, where members of both state populations often say they are being oppressed by even more powerful national populations. On the other hand, the UU is situated in a city that tends to vote Democratic and that has a diversity of religions and non-affiliated populations, where often these local populations also feel oppressed by the majorities in the larger state.

To add to this complexity, each PCS student, staff, and faculty member experience these circles of power differently, based upon their own political, religious, cultural, and other intersecting identities.

Figure 1

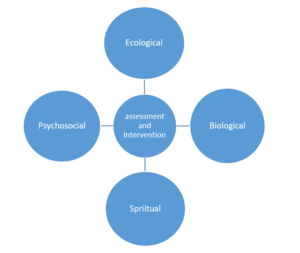

What is the Ecobiopsychosocialspiritual life-long development perspective?

The PCS discovered that our students quickly grasp the Ecobiopsychosocialspiritual (EBPSS) perspective and can apply it when assessing conflict situations. This perspective is an inclusive approach to peace practice, that helps students include the many factors that contribute to conflict situations. Students learn to consider all dimensions when assessing and engaging, and intervening with people (see Figure 2).

“Eco” or Ecological, is about the “Big Picture”, and refers to the environmental context of the situation to be assessed, including factors such as global and local community, family and cultural backgrounds, and environmental factors.

“Bio” or Biological refers to the physical dimension of wellbeing, including nutrition, disease, environmental toxins, sanitation, and availability of clean air and water.

The Spiritual dimension includes the sense of connection people have with each other and the world, the lifelong development of consciousness (or reverent awareness), and the ability to express loving kindness towards self and others.

The Psychosocial combines both intrapersonal factors (such as beliefs and emotions) as well and interpersonal factors (such as family relationships, relationships with colleagues, and online experiences). PCS faculty separate these two factors out when discussing case studies.

Figure 2

Case example: Applying the Ecobiopsychosocialspiritual perspective in a conflict resolution case

Any human conflict can be analyzed from an EBPSS perspective. For example, some of PCS students seek a career working with the court system, doing divorce mediation work. One student brought in a case involving a couple who wanted to get a legal divorce, but who were in conflict about how they viewed each other and the marriage. “Bill” had brought in two children from a previous marriage, and he also had owned the house that the couple resided in. Bill shares custody with the children’s mother Ruth, who is upset that Bill no longer attends church with the children. Bill’s husband “Marcos” was 10 years younger than Bill and complained that Bill was a “control freak” who also had a drinking problem. Bill said that Marcos was “immature” and always “bummed”. Both Marcos and Bill agree that they yell at each other “too much” although they do not report any physical violence.

We looked at the case from an EBPPS perspective. From the ecological viewpoint, for example, the students discuss the heterosexism that same sex couples have to deal with in our society, and how heterosexism might impact the marriage and divorce. The students also considered the economic and housing conditions in the couples’ life.

From a biological viewpoint, we looked, for example at Bill’s drinking, and how that is may be associated with the couple’s current challenges. An example of the psychological level might be an analysis of Marcos’ possible depression, and the verbal violence in the couple’s relationship is a social issue. Finally the conflict between Bill and Ruth about church is an example of a spiritual level issue.

Finally, ressentiment can be understood and worked on from the EBPPS perspective. There are many factors that could contribute to traits of ressentiment in an individual. On the ecological level, increasing disparity of income and wealth in countries like the USA could be a factor. On the biological level, the lack of access to healthy foods could be a factor. The individual’s own tendency towards resentment is a psychological factor, and her relationships with other people could influence her ressentiment on the social level. Finally, the individual’s ability to find meaning in his suffering and to disidentify with (let go of) his need for power and wealth is an example of a spiritual level factor.

Experiential learning

The PCS believes that the education is “serious play” in which students to discover their own voice, their compassion for others, and their wisdom, through engagement with themselves, each other, and the world. Most courses that count towards the PCS major and minor are traditionally-taught academic classes from across the University. The required PCS courses (Introduction, Dialogue practice, and Integrative seminar) all utilize nationally recognized textbooks that students are asked to read and react to.

Academic rigor is not limited to assignments that challenge students to achieve cognitive development. In the PCS classwork, students are challenged to rigorously develop their social and emotional intelligences. PCS uses “real plays”, structured interactions where students engage in dialogue with each other. Instead of asking students to role play a fictional example of a conflict in the workplace, students are asked to volunteer a real experience they encountered.

Any teaching content can be taught experientially. In order to teach the concept “deep peace”, an instructor could construct a power point and show examples of peace (the lack of violence) and deep peace (not just a lack of violence, but also active dialogue, compassion, cooperation, community). An experiential approach to teaching about deep peace would be, for example, to first ask students to share in dyads or small groups about the most peaceful and the least peaceful communities that they experienced. Then, back in a large group, students volunteer traits of very-peaceful, peaceful, and not-so-peaceful communities. Patterns of peace and deep peace usually emerge on the white board from this kind of discussion.

Intergroup dialogue

PCS uses intergroup dialogue in classes, an experiential form of learning that combines intrapersonal and interpersonal consciousness work. Dialogue is a relationship- and community-building alternative to debate that can help people bridge the differences that often divide. In the required dialogue class for PCS majors and minors, students first study dialogue processes, including their own hidden biases, their emotional triggers, and their identifications with different beliefs. In the last 10 weeks of the semester, students host groups of people for in-classroom dialogue. These are groups that students’ have identified as populations that they tend to dislike and even demonize. Often these groups represent different races, religions, political affiliations, and sexual orientations.

PCS developed a set of dialogue ground rules (See Figure 3, from Derezotes, 2016) that help guide these difficult conversations. Evaluations of these dialogues show that students value these sessions and learn valuable lessons that they later apply to their personal and professional lives. PCS believes that one of the true marks of an educated person is that she or he can have a dialogic conversation with anyone in their community.

Figure 3: Dialogue ground rules

Do:

- Listen for understanding

- Speak respectfully

- Speak for myself

- Offer amnesty

- Wait at least three turns before speaking

- Own my own biases judgments and projections

- Do not:

- Interrupt

- Make negative gestures

- Make others wrong

- Do side talk

- Do teaching and preaching

A dialogue might be used as an experiential approach to teaching ressentiment. For example, students can be put into a circle. The instructor models the role of facilitator, using the ground rules above. The instructor might have students take turns going around the circle. In the first go-around, each student can share a trait of ressentiment that they have observed in another person. In the second set of turns, students might be challenged to own a trait of ressentiment that they themselves have.

PCS internships are another opportunity for experiential learning. All PCS students’ taking a PCS major, and most of the minors, enroll in a PCS internship. At the beginning of the internship, students are asked to reflect and report on their learning goals. When the internship is finished, students’ complete a report report reviewing what was learned, and what they want to focus on next in their educational and vocational trajectories.

Conclusion

Can we accelerate the “technology” of peace, and keep pace with our advancing technology of war and destruction? The UUPCS program, like many others now being taught or developed in the world, is a sign of hope that humankind is capable of learning about peace. PCS wants to face the fact that people live in an era where we are all challenged to learn how to deal with conflict peacefully. PCS views the program as an ongoing experiment, continually evaluated, in hopes of “getting it right” for students, and local and global communities.

References

Derezotes, D.S. (2014) Transforming historical trauma through dialogue. Los Angeles: Sage.

Krishnamurti, J. (1996). Total freedom: The essential Krishnamurti. Ojai, CA: Harper One.

Mishra, P. (2017) Age of anger: A history of the present. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.